Here’s video interview 3 of 4. Evelyn and I discuss: Is Juliana really virtuous? And what might the Characterists and Personalists represent in our real world?

Here’s the transcript (the video also has subtitles, but I’ve just played it and realized that the compression makes them unreadable anyway):

Q: Juliana does an excellent job delivering deadpan innuendo. Is she really so virtuous?

A: Well, she says herself she’s not necessarily virtuous entirely by her own choice. She considers herself unattractive, and so her lack of involvement, as it were, is not necessarily her own idea. But she appreciate’s Bass’s… attention, and his low-pressure approach, his own sense of what’s right and proper.

Q: But her comments do suggest that she’s certainly not naive.

A: No, no. She’s definitely not naive, she’s probably the smartest character in the book, in fact.

Q: And there’s her having a title at the end, gaining a title at the end. Which she does, I imagine, gain?

A: Yes.

Q: Beyond the last page.

A: Yes. Yes, she kind of makes up for Bass’s innocence. She’s the counterbalance.

Q: Would you say that there are non-fictional equivalents to the Personalists and the Characterists in your story?

A: I’ve been thinking about that. They were – in terms of the politics, they were based on the factions which were at war in Renaissance Italy, the Guelphs and the Ghibbelines, I’m not sure if that’s the correct pronunciation, who had… the supposed reason was different views on how bishops should be appointed and the power of the Holy See, but in practice they were political. Or on Catholics versus Protestants through most of the Reformation. But the more I think about it the more I think it’s my metaphor for modernists and postmodernists on the one hand and whatever it is that I am on the other hand. Which… I’ve been using the term “transmodern” for lack of a better one.

Basically I see modernism and postmodernism as emptying, deliberately emptying out a lot of meaning out of life, out of things in general, and particularly modernism is saying, if you can’t measure it, if it’s not scientific, it has no meaning, out with it! And then postmodernism comes along and says, “Look! Everything’s empty!” Whereas transmodernism says, “Well, actually, it’s empty because it’s been emptied. And you should maybe examine your assumption that there is nothing but the mask, that there is nothing but the superficial, that there is nothing but what you can see and touch, and that there might actually be something behind that that’s real.”

Q: It sounds a lot like the shadows on the wall of the cave.

A: Yes, yes, I suppose. And one of the reasons I think that I chose a late-Medieval/early-Renaissance setting is that I quite like the thinking of that time in terms of the reality that they saw underlying the external and the superficial, and that was lost in the subsequent “enlightenment”, so called.

But obviously we’ve been through the Enlightenment, we’ve been through the 19th century, we’ve been through the 20th century, we can’t go back. We can’t suddenly become medievals again. And nor would we necessarily want to. So I suppose I’m saying, “Let’s look at some of the things that were emptied out about culture and see if we can put some of them back again.” In a transformed form, because you can’t just go backwards.

Q: No. And can you think of an example of one of those things that you’d like to see put back in?

A: Well, one thing that the 20th century notoriously emptied out was the value of the human person. And you only have to look at 50 million people killed in World War II, at the atrocities in places like Cambodia, Uganda, to see that. And Bass is speaking for me when he says, it doesn’t matter if the High Priest is a good man or a bad man, if you like him or don’t like him, he’s a human being. You need to protect his life because he’s a human being. It’s wrong to kill him.

Q: So in that way does Bardo represent what is to come in your hopes, in your wishes after postmodernism? Is Bardo taking us into the next movement, so to speak?

A: Ooh. Ah. Bardo’s rather ruthless, and as Corius says I don’t think he necessarily considers the value of a human life to be inherent. No, I don’t think Bardo’s taking us forward.

Q: No? Even though he presents a whole lot of hope for the City of Masks?

A: He does, he does, but the hope that he presents is a hope that goes backwards. He’s a hard-line, old-style monarch turning back the clock, and I don’t think that’s the way forward for us.

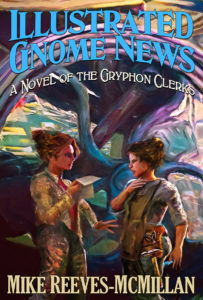

Mike Reeves-McMillan lives in Auckland, New Zealand, the setting of his Auckland Allies contemporary urban fantasy series; and also in his head, where the weather is more reliable, and there are a lot more wizards. He also writes the Gryphon Clerks series (steampunk/magepunk), the Hand of the Trickster series (sword-and-sorcery heist capers), and short stories which have appeared in venues such as Compelling Science Fiction and Cosmic Roots and Eldritch Shores.