Like millions of other fans, I’m saddened to hear of the death of Sir Terry Pratchett, one of my favourite authors. It seems like a good occasion to reflect on humour in SFF (science fiction and fantasy), a topic I’ve been thinking about lately in any case.

I recently read, or at least started to read, a single-author collection of supposedly humourous SFF. The humour didn’t work for me, as sometimes happens, and what that revealed, like mudflats at low tide, was that the stories weren’t particularly good stories, and the SFF consisted mainly of cliches (while the humour consisted mainly of silly names). I didn’t make it past halfway through the second story, a limp Lord of the Rings parody, neither funny, nor well-written, nor interesting.

I see this a lot in would-be comedic writing. I have to admit, as a reviewer I do often grant an author a pass for a dubious bit of worldbuilding, plotting, characterisation or what-have-you if the writing makes me laugh. The risk you run when you rely on this, though, is that if the writing doesn’t make the reader laugh, there’s nothing left to fall back on.

I maintain that a big part of the reason that Pratchett was the preeminent comic novelist since P.G. Wodehouse, responsible at one time for almost 4% of the entire British publishing industry’s sales, was that he wrote books that worked as stories. His characters in the early books may have been cliches and stereotypes, but by his long and productive middle period he was writing characters with depth, complexity, growth and development.

There’s a subtle, but detectable, gradient from cliche to stereotype to parody to character trapped in an unfortunate pattern of behaviour by habit and social expectation, and Pratchett showed us the full spectrum in the course of his career. He was an insightful observer of humanity, as all the best comedians are, but he was also a compassionate one – not just holding people up to mockery but reminding us that, whatever their failings, however small-minded and ridiculous they might be, they deserved consideration as human beings. (Even when they weren’t, strictly speaking, human beings, but dwarves, trolls, golems, vampires, Igors or goblins.)

He’s often compared to other writers, most frequently Douglas Adams and P.G. Wodehouse, but his stories have more depth than either. In Adams, there are cosmic stakes, but they’re minimised by the absurdity. In Wodehouse, the stakes are seldom higher than social embarrassment. In Pratchett, the stakes are high, and we care about them, and yet we’re laughing.

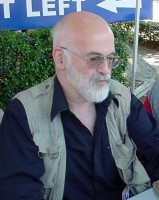

- Sir Terry PratchettRaeAllen / Foter / CC BY-NC-SA

I’ll make a comparison myself. There’s a fairly obscure American humourist called Damon Runyon. Most people who’ve heard of him know him through the musical Guys and Dolls, or perhaps the Shirley Temple movie Little Miss Marker, both of which were based on his work, but he wrote a great many short stories in the 1930s set in the more dubious parts of contemporary New York. They’re stories of revenge, lost love, family tragedy, violence and, occasionally, good triumphant with the help of rough, hard-bitten characters who have a sentimental side. Yet, mainly through the voice of the unnamed narrator (who observes much more than he participates; he’s never unambiguously the protagonist), they’re funny, both because of their wry, ironic observations and because of the distinctive language. They are, at the same time, slangy and poetic, and characterised by a total avoidance of the past tense.

My parents had an omnibus of the Runyon stories, and I read them a couple of times growing up. A while ago, frustrated by another would-be comic fantasy that I didn’t find funny or otherwise enjoyable, I set out to write my own version of the same premise, and for reasons connected with that premise I picked the Runyonese dialect to tell it in. To make sure I was getting the voice right, I re-read some of the Runyon tales, and I was struck by the fact that there’s often a dark, or at least heartwrenching, story going on behind all the humour. So I strove to make that, too, a part of the story I wrote, which you can read here.

I might never have thought of attempting that, though, if it hadn’t been for the example of Terry Pratchett. Death (the phenomenon) isn’t funny. Death (the character, who makes at least a cameo appearance in every Discworld book and is a main character in several), while usually serious himself, is a cause of comedy in other people.

Let’s reflect on that for a moment. At least one person dies in every Discworld novel. Often, it’s a minor character, but usually it’s someone with a name, though sometimes we don’t learn the name until Death says it in all caps. And these are primarily thought of as comic novels.

That, too, was part of Pratchett’s genius. Nothing in life, not even death, was outside his warm, human, comedic insightfulness. Now that he has made the transition himself, it’s up to us who are left to try to carry on his legacy, not only of funny fantasy, but of kindness, good storytelling, and reflection on the human condition.

Mike Reeves-McMillan lives in Auckland, New Zealand, the setting of his Auckland Allies contemporary urban fantasy series; and also in his head, where the weather is more reliable, and there are a lot more wizards. He also writes the Gryphon Clerks series (steampunk/magepunk), the Hand of the Trickster series (sword-and-sorcery heist capers), and short stories which have appeared in venues such as Compelling Science Fiction and Cosmic Roots and Eldritch Shores.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.