“What do you mean, leave?”

“What do you mean, leave?”

“Leave. Go somewhere else,” said Stone.

“Why would you want to do that?” said his father.

“Well, let’s see. Fern’s going to inherit the farm…”

“Which you agreed to.”

“I did, because I’m perfectly happy about it. I don’t want the farm. She’ll run it a lot better than I ever would, but the fact remains, I don’t really have a place here.”

“Of course you do.” Stone’s father scratched his bald spot. His sleeves, still rolled up from the day’s work, showed thick, hairy forearms to match his heavy body. He rested them on the scrubbed table in the stone-flagged kitchen where all family business was done. Neither Stone nor his father was tall, and Stone very much suspected that when he reached his father’s age he’d look exactly like him.

He wouldn’t, however, be like him in other ways.

“What I mean, Father,” he said, “is that I want to go out and experience life, see the world.”

“Our family’s farmed this valley for generations.”

“Yes, exactly. And nothing’s changed here for generations, either.”

“Oh, you know that’s not true. Just in the last ten years, we’ve brought the average yield per cow up by a clear sixteenth, and the butterfat…”

Stone sighed. “Father,” he said, “I don’t care about butterfat.”

Faced with this incomprehensible heresy, Stone’s father sat speechless, his mouth hanging open. A cow-follower bird called outside the window, and its mate answered: pwit pwit pwit, tee-yip, tee-yip.

“I… I just want a chance to see other places,” said Stone. “Other ways of living. I’ve never felt like I fit in here.”

“How can you not fit in here? You’ve never lived anywhere else.”

“Father, that’s exactly the point I’m making. I want to try living somewhere else and see if… see if I’m happier.”

“Well,” his father said, “I don’t understand it. But you’re an adult now, so I suppose you can suit yourself.” He turned his head aside and didn’t look at Stone, and Stone knew he’d offended him.

“Father,” he said, “I’ll appreciate this place a lot better, I’m sure, if I see what other places are like. I just… I want to leave. For a while, at least.”

His father nodded, still not looking at him. After a moment, Stone stood and went to find his sister Fern. She wouldn’t understand either, but she’d support him, at least.

Stone stood by the dock, clutching his bag, while the cheese-boat loaded and prepared to depart. Only Fern and Father had come to see him off.

“Where’s your friend?” said Fern. “Bark? I would have thought he’d come.”

“Well,” said Stone, uncomfortably, “Bark’s busy now that he’s courting River. He… we don’t see each other much any more.”

“That’s a pity. You used to be close,” said Fern, and Stone’s heart lurched, thinking about just how close they used to be, and how that had ended when Bark’s family decided it was time he was oathbound and started pushing him towards River. At least Stone’s father, for all his faults, had never insisted on that.

“Well, take care,” said Father, his gruff voice even more congested than usual. “Write as soon as you get there and let us know how you’re getting on.”

“Thanks, Father,” said Stone, and they clasped big, hairy hands. He kissed his sister on the cheek, and she pushed a small packet into his hands.

“What’s this?” he asked.

“Keep you going for a bit,” she said.

“It’s money?” he said, shaking it.

“Little bit. We had a good year, and you worked hard.”

“Thanks, Sis.” He embraced her, and the captain called, “Prepare to cast off!”

“Better go. Thanks again!” he said, and hurried to climb aboard the river craft.

They all waved until after the boat had passed the bend and they couldn’t see each other any more.

The boat stopped in Riverbend Market, capital of the Eastern Province, on the way downriver. Stone had been up to High Rapids, the capital of his own Inner Province, once, and couldn’t help contrasting that prosperous, tidy city with the scruffy appearance that Riverbend Market presented.

“Not much wealth in Eastern,” said the captain, when he remarked on it. “Rough country, hilly, not like those plains you have up north. All they run here is sheep.” They took a barge full of raw wool bales in tow for the rest of the trip down to Gulfport. “Don’t want it on the boat,” said the captain, “the stink gets into everything.”

Even Riverbend Market, though, couldn’t match his first sight of Gulfport. The capital city was… grand. That was the word, he decided. Everything seemed on a larger scale, from the wide streets to the tall buildings. Even the street trees looked bigger.

As he stared around, the captain cleared his throat beside him, then laughed when he jumped. “You got arrangements?” the man asked. “Place to stay? Work?”

“Not yet,” he admitted.

“What are you looking for in the way of work?”

“I… don’t know yet. Something that has nothing to do with cattle.”

The captain snorted. “That would be pretty much everything. You read and write?”

“Of course,” said Stone. The school at home was excellent, and prepared students for the correspondence college, which taught animal husbandry, agricultural methods, the basics of accounting and business as it applied to running a farm, and a little theory of lifemagic.

“No ‘of course’ about it,” said the captain. “You might oughta look into this thing the new Realmgold’s started.”

“What’s that?” said Stone. He’d heard the news, of course, that Victory, the Provincegold of Western, a woman about his own age, had recently been elected by her fellow Provincegolds to succeed old Glorious.

“She needs clerks to help her make her changes,” said the captain. “She’s started a college for them up in Illene, that old elven city we passed a ways back.”

“I don’t know if I want to be a clerk,” said Stone. It didn’t sound very exciting.

“Oh, it’s not just pieces of paper, what I hear,” said the captain. “You look into it, young fella.”

“All right,” said Stone, not intending to do any such thing.

They docked, and there on the wharf stood a booth with an awning, and a row of men and women sitting behind a table. A banner stretched across the front of the awning said “Recruiting” accompanied by a picture of a stick figure with a shovel, the widely-understood symbol for “workers wanted”. At the front of the table, five smaller banners held large icons, presumably intended for the illiterate. He saw the military (a sword), mages (a bracelet), healers (a round hat), and the figure with the shovel again, indicating general hiring, but the fifth one was unfamiliar: a beast with a lion’s body and tail, but with the lion’s foreparts replaced by an eagle’s head, body, wings and talons. Curious, he approached the woman at that table.

She smiled brightly and asked, “Can I help you, sir?”

“What is it you’re recruiting for?” he asked.

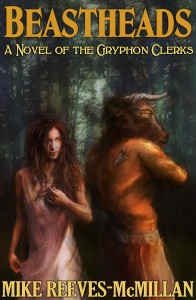

“This is the Gryphon Clerks,” she said, touching a silver seal hanging around her neck. “We’re Realmgold Victory’s eyes and hands, and voice when we need to be. Have you heard about her reforms?”

“I’ve heard my father complain about them,” he said.

“Well-off, is he, your father?”

“We didn’t want for anything,” he said. “I wouldn’t call us rich.”

“No offence intended,” she said, “it’s just that most of the opposition to the reforms comes from people who were doing well under the previous Realmgold. The new Realmgold wants to spread the prosperity around more, and not everyone who has it now is happy about that.”

“Because it will come at their expense?” he said.

“Not necessarily. More that they’re used to being on top, I think, and don’t want anyone else coming up and joining them. But enough politics. Can you read?”

“Yes.”

“Fluently?”

“Yes.”

“Read this for me,” she said, and handed him a book. He read the passage she indicated aloud without difficulty.

“You fancy being a Gryphon Clerk?” she said.

“I don’t know. What’s it involve?”

“Oh,” she said, “travel, if you want. Meeting new people. Convincing them to take part in what the Realmgold is doing.”

“You know,” he said, “I might look into that.”

“Here’s a pamphlet,” she said. “Sit over there and read it, and come back if you’re still interested.”

Within an hour, he was on a ferry back the way he’d come, heading for the Clerks’ College in Illene.

Three years later, Stone returned to Gulfport to work in the Office of Trade and Industry as a junior clerk.

At his interview, the Leading Clerk who hired him had strongly implied that if he worked hard and did good work he would have a chance of travelling later on, and since he still wanted to see new places he gave the job his best, even when it fell into routine — as a junior clerk’s work inevitably did.

Promotion was rapid in the Clerks for good workers, and he soon managed to drop the “junior” and become a full clerk, transferring to the Northern Office, which dealt mainly with the neighbouring realm of Denning.

There, at the next desk, he met Glorious of Littlemeadows.

Named after the previous Realmgold by his ultraconservative father, Glorious had rebelled against family expectations by joining Victory’s Gryphon Clerks. “And so Father won’t talk to me,” he confided to Stone, “which was exactly what I was setting out to achieve. What about you? Do you talk to your father?”

“I send him letters,” said Stone. “We don’t see eye to eye on a lot of things, but… we stay in touch.”

Glorious nodded. He was everything Stone wasn’t: tall, slender, handsome, refined, a member of the Gold ruling class and, at least nominally, of the Asterist religion. He was fascinated by Stone’s name.

“I thought it was only peasants who had Earthist names,” he said.

“I suppose strictly speaking we are peasants,” said Stone. “I mean, we’re farmers. Well-off farmers, enough to count as Silver class by income, anyway, but that’s really all that distinguishes us from the Coppers.”

“Well, that and education.”

“Victory’s encouraging education of the Coppers,” Stone pointed out.

“Oh, true, and how wonderful of her,” said Glorious. All the Clerks took a loyalty oath that bound them to Victory and the realm, so they tended to think highly of her, but Glorious behaved as if she made the sun come up each morning.

Glorious came in one morning to find Stone already at his desk. “You’re in early,” he said.

“I wanted to get to work on this file,” said Stone.

“What is it?”

“Trade figures. Takes concentration, you know, and I thought if I was in here by myself I could get a good start on it.”

“Oh, do I distract you?”

“No, no,” said Stone, which wasn’t true. “It’s just that when the office is quiet, it’s easier to sustain a line of thought all the way to the end.”

“Quite,” said Glorious. But Stone noticed that he didn’t talk to him as much the rest of the day, and wondered if he’d offended him.

It was Threeday, the day before the usual day off, and when the time came round for the office to close, Glorious stretched his long limbs and cracked his knuckles.

“Well,” he said, “I’m for the tavern. Coming?”

“Me?” said Stone.

“Why not? I’ll drink in a tavern with any man. You more than most, if anything.” He grinned, and Stone grinned back. He must have just kept quiet out of consideration, Stone thought.

“What would your family think of you going drinking with a Copper?” he said, pulling on his coat.

“You’re not a Copper. Gryphon Clerks are Silver class. But I don’t care what they would think, as I’m sure you’re well aware.”

They stayed at the tavern late into the evening, sharing a bottle of wine and a meal. They started out talking about Leading Clerk Felicity and the other clerks they worked with, but soon Stone was telling Glorious about growing up on the dairy farm and how boring it had been, and Glorious was talking about being bullied at the Academy of the Triple Star.

“All the Golds send their children there,” he said. “The upper end of the Silver class, too, the ones who want their grandchildren to be Golds. We’re supposed to make alliances and connections that will last us the rest of our lives.”

“And did you?”

“I’ve never seen a single person from there since I walked out the gate on my last day,” said Glorious. “Never wanted to, either. Graduation from the Academy counts as adulthood rites, and I walked straight over to the Clerks’ College and signed up the same afternoon.”

“What did your family do?”

“Oh, there was a huge row, but there was nothing they could do about it. I don’t see any of them, either.” Glorious leaned back as he spoke, and gestured largely, like a man who didn’t care, a man who had put his past behind him.

Without further discussion, the tavern became their regular Threeday destination after work, a place where they could talk about their dreams and plans over a meal and a bottle of good wine. Glorious wanted to be a diplomat, “somewhere exotic, you know, to the centaurs up in Coriant or something”. Stone wasn’t sure exactly what he wanted, but he knew he wanted to see more of the world. Perhaps, he thought, he and Glorious could go and see centaurs together.

One night, when a second bottle had joined the first, Stone eyed his friend with an unsteady gaze and said, “You know, you never speak about any plans to get oathbound.”

“Oh, well,” said Glorious. “I don’t really have any. I mean, young yet, and so forth, right?”

“You don’t speak about women either, though,” Stone persisted.

“Well, no more do you.”

“Ah, well, the difference is, though, women speak about you. I’ve heard them, you know. And you are a handsome fellow, there’s no denying it.”

“Thank you,” said Glorious, and glanced around the tavern. They were among the last people there, and nobody else was paying any attention to them. “Tell you something,” he said, leaning in and dropping his voice.

“What?”

“I don’t really like women. I mean, I like them all right as people. But not as women, if you know what I mean.”

“I know exactly what you mean,” said Stone, filled with hope (and wine). “Exactly.” He reached out and covered Glorious’s hand with his. Glorious looked at it, looked up at Stone, and they both burst into laughter.

Someone like me at last, thought Stone. And he’s so handsome.

That was Stone’s last clear memory when he woke, hung over and stinking of his own vomit, on a bed of straw in a stone cell. A wooden bowl of cleanish water stood nearby, and after taking a few minutes to get his body back into working order, he crawled over to it and drank.

It did something for the dry mouth, not much for the headache, and stimulated another urge, the receptacle for which was in the opposite corner of the cell. He managed to get most of it in the pot rather than on the floor, and staggered back to the straw, where he tried, around the headache, to puzzle out what had happened. He seemed to have some bruises that he couldn’t account for.

With a headsplitting crack, the hatch in the cell door flew back, and a man peered through the barred window thus revealed. He wore a military fore-and-aft cap with warden’s markings .

“You awake?” he said.

“I think so,” said Stone.

“Your boss is ’ere to get you out,” said the warden, and Stone groaned, for several different reasons.

Mike Reeves-McMillan lives in Auckland, New Zealand, the setting of his Auckland Allies contemporary urban fantasy series; and also in his head, where the weather is more reliable, and there are a lot more wizards. He also writes the Gryphon Clerks series (steampunk/magepunk), the Hand of the Trickster series (sword-and-sorcery heist capers), and short stories which have appeared in venues such as Compelling Science Fiction and Cosmic Roots and Eldritch Shores.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.