I haven’t blogged for quite some time, and for the best of reasons: I’ve been writing the next Gryphon Clerks novel.

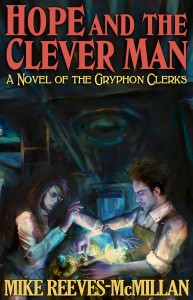

Actually, I’ve been writing the one after next. The next one (Hope and the Clever Man) is with my beta readers, and while I waited for their feedback I had some ideas for the sequel, and as I write this post I’m about to pass 70,000 words – all written since I started nine weeks ago.

This is a surprise. I’ve not written this fast or this easily before. I think it’s because I’ve never written a series before, and now that I have a good run-up, and the characters and world are clear in my head, they’re producing the story for me much faster.

Now, I know that I am actually producing the story. It’s a useful fiction to say that the characters are doing it. Useful, because it describes the experience I have when I’m writing a scene and a character suddenly starts talking about a painful experience earlier in his life that I was not expecting him to mention in this context, one that I knew would eventually come up but which I hadn’t worked out in any detail, and I’m writing away thinking, “I wonder what happens next?” And as I continue writing, I find out. That happened in the new book, and it was wonderful.

Although I’m making more use of outlining than I used to, I’m still what’s politely called a “discovery writer”, which means that for me, story generation happens mostly while I write. This has its drawbacks, in that I don’t always know what happens next and can get stuck, but it also has its advantages, in that I don’t always know what happens next and can be pleasantly surprised.

One of the surprises has been that Hope and the Patient Man (the current work-in-progress, sequel to Hope and the Clever Man) turns out to be a romance. I did not see that coming, though I probably should have, given the young man who turns up, unexpectedly to everyone including me, late in the first Hope book.

One of the current kerfuffles in the spec-fic field is over an article by an academic named Paul Cook on the Amazing Stories website called When Science Fiction is Not Science Fiction. In it, he basically says that he likes adventure stories, and that is what science fiction is, and ones with romance in them are for girls and not real SF. It’s not a sophisticated argument, and rather than dignify it by linking to it I’ll link to Lois McMaster Bujold’s excellent commentary on the issue. (I’ve chosen the Goodreads version of her post, because she also has some interesting exchanges in the comments.)

What I write, of course, isn’t science fiction by pretty much anyone’s definition, including mine (though it’s more sciency than most fantasy; I do have an approximate theoretical basis for the magic which kind of maps to some real-world science if you don’t look too closely, rather than just saying “a wizard did it”). It’s steampunkish fantasy, and to that I now need to add to the word “romance”, apparently.

- Thomas Hawk / Foter / CC BY-NC

Some things about that. Firstly, it turned into a romance because I think relationships are important. I’m married (15 years come February), and that relationship is extremely important to me. A friend of mine, who I met on our first day of high school in early 1981 and have stayed in touch with almost continuously since, has recently moved back into the same country as me, and bought a house in the same city that I live in, and we’re hanging out, and that’s reminded me of the importance of friendships for helping define who we are. How relationships define us is a bit of an emerging theme in the second Hope book, in fact.

It’s often said that characters are defined and revealed by taking action, by what they do in response to circumstances, and that’s true. It’s especially true in an action novel. In a novel that has more to do with relationships than with adventure, though, it’s also true that characters are defined and revealed by their connections to one another.

These are not exclusive categories. There are novels that are high-action and low-relationship, and vice versa, but most occupy some kind of middle ground, especially in the spec-fic field. Some of my favourite characters, like Lindsay Buroker’s Amaranthe Lokdon, Carrie Vaughn’s Kitty Norville, and (to choose a male character by a male author) Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden, are remarkable because of their ability to collect people who are linked to them by ties of friendship, or at least shared interest, and who act as force multipliers for the characters when they want to get something done.

I’m grateful to the pioneers of the New Wave in the late 60s and early 70s for injecting more relationship into what had been a largely action-oriented genre, because personally I find relationships interesting as well as important. At the same time, I’m not going to go all Paul Cook and claim that only novels that deal with relationships are X (where X is members-of-genre-I-like, good, enjoyable, valuable, or other, as Lois McMaster Bujold puts it, valorising adjectives).

I do want to say a bit about romance as a plot element versus romance as a genre category, though. Romance as a plot element appears in all genres. Romance as a genre category has its own tropes, its own rules, its own recurrent themes, and I’m not planning to take all of those on in my writing.

I’ll freely admit that I’ve read hardly any genre romance, and am poorly qualified to comment on the genre as a whole, so I won’t. I will mention, though, particular kinds of romance that I find in other genres I do read, such as steampunk and urban fantasy, and some of the problems I have with them, and why I won’t be doing that.

Before I do, though, I think it’s uncontroversial to say that romance is largely written by women. Men who write it sometimes use feminine pen names, just as women who write science fiction sometimes take masculine pen names (or use their initials rather than their names). I’m not going to talk right now about whether that’s good or bad or problematic; it’s a thing that happens. Now, I’m a man (a cis man, if you like, meaning I was born male and have always identified as such; also a straight man; also a white, middle-class man, and yes, that’s relevant). It would be somewhat surprising, our society being what it is, if I approached writing about relationships exactly the same way a woman would, because I’ve been raised with a different perspective.

I also identify as a feminist ally, and as such, I find some of the romance plots I encounter in steampunk and urban fantasy problematic. Tracing, no doubt, a lineage back to Mr. Darcy and Heathcliff, among others, the “heroes” of these romances are often unpleasant human beings. They treat women poorly, but are forgiven because they rescue them when the women do foolish, headstrong things that place them in danger, and because they have firm muscles that make the heroine’s heart beat fast despite herself.

Now, I understand that there has to be a reason why the couple doesn’t just get together right away, otherwise what you have is not a plot, but an incident. However, it’s not essential or inevitable that this reason should be “it’s actually a bad idea to be with this guy”. To me, that’s simultaneously naive and cynical: naive, in expecting a relationship with such a flawed man to work out anyway, and cynical, in that it assumes that men don’t get any better than that.

I’m not going to point to examples of what I’m talking about, because they aren’t that hard to find and I don’t want to single out individual authors just because I’ve read them, when there are much more egregious examples that I haven’t read. I will, however, point to a counterexample, an urban fantasy series in which there’s a strong romance thread, in which there’s a clear reason why the couple doesn’t get together straight away, in which it’s not because he’s a cad and a bounder and a deceiver, in which the woman has agency and makes smart decisions and can rescue herself quite competently. I’m talking about Christine Amsden’s Cassie Scot series. This is how you do it! </Randy Jackson>

So, anyway, the romance part of my writing works like this. There’s a magic-based but in other ways realistic reason why the couple can’t just get together. They work on it together, because he’s a decent guy and thinks she’s wonderful and worth the effort, and she appreciates this. Along the way, he contributes to resolving some other issues, both inside and outside her head, but she is ultimately the one who has agency. He’s not trying to control her or live her life for her.

Part of the way that stories work is that they help us develop problem-solving skills. I have a real concern about some of the romance stories that are around, for that exact reason. So if my book is turning into a romance, I’m going to give my perspective – as a man, happily married to a woman with a master’s degree in marriage and family therapy, who’s also studied some psychology himself – on what a good relationship looks like. My hope is that it educates while entertaining.

In case it’s not clear from what I’ve said above about my writing process, I’m not forcing this stuff into the book. It’s coming up by itself, because I’m following the old principle of “write what you know”.

If all goes according to plan, you should be able to read Hope and the Clever Man sometime around November this year, and Hope and the Patient Man early next year. To get announcements when they’re published, sign up to my (low-volume) mailing list in the sidebar of the site.