I’ve worked on books in three different series, with three different settings, in the past few months. This post is a reflection on how the writing experience differed between them, and how the settings contributed to the stories I told in them.

The three series are Auckland Allies (contemporary urban fantasy, set in the city where I live); Hand of the Trickster (sword-and-sorcery heists); and the Gryphon Clerks (secondary-world lightly steampunked fantasy). Yes, I know my last post said I probably wouldn’t be working on any more Gryphon Clerks stories in the foreseeable future. The future is a lot less foreseeable than I thought, as it turns out.

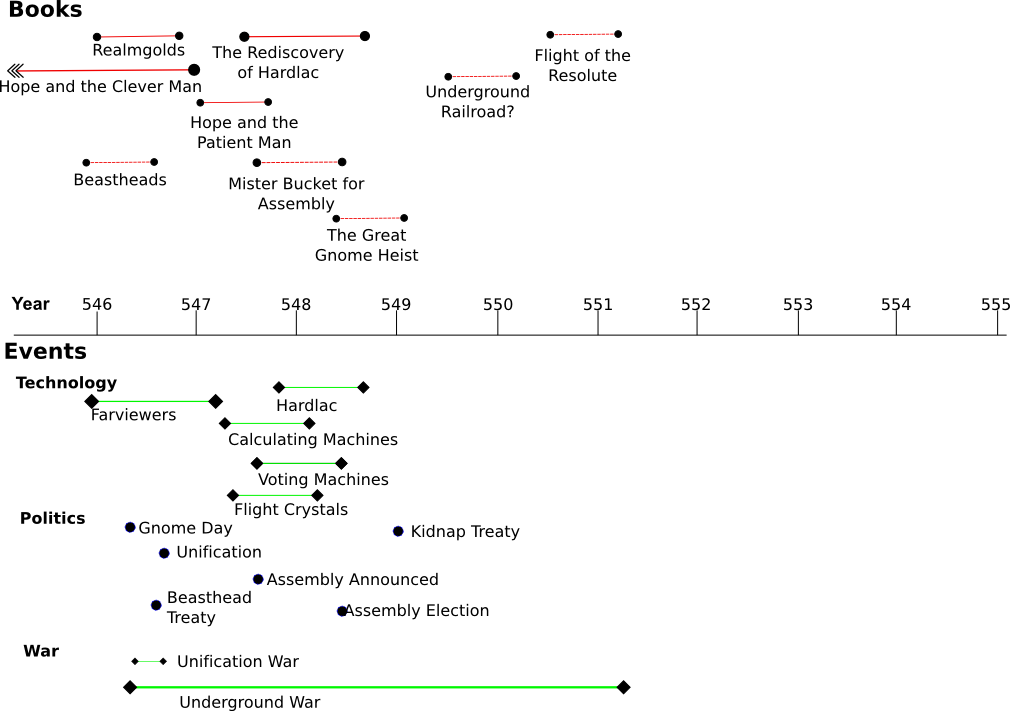

Part of the reason for having different series going is that a change is, in fact, as good as a rest. Because they feel different to work on, I can work on one when I don’t feel like working on another, and switching from one to another can be refreshing. In fact, the reason I got out my abandoned manuscript of Mister Bucket for Assembly, the Gryphon Clerks novel (which turned out to be about 75% complete), was that I was making slow, difficult progress on the second Hand of the Trickster book. I was soon happily logging 3000 to 5000-word days on Mister Bucket, where I’d struggled to reach 1500 words some days on the other book.

Let’s see if I can identify what it is about each of these series that feels different, what attracts me to write in the settings, and what those settings contribute to the fiction.

Auckland Allies

The fun thing about Auckland Allies is that it takes place in a setting I know well: the real-world city of Auckland, New Zealand, where I was born and, where, apart from an eight-month period in Brisbane many years ago, I’ve lived ever since. That means that I can celebrate the things I enjoy about the city; work in a few complaints about it; and research my books just by walking around (or using Google Maps and Street View, in a pinch).

It also provides its own inspiration. For the first book, I strapped a GoPro camera to my head and walked through places where I’d set chase scenes, and that gave me additional ideas for those scenes and how they could go. I also used the extinct volcanoes which are a unique aspect of Auckland to make it a story that couldn’t be set anywhere else.

Graves under Grafton Bridge (my photo)

The second book, Ghost Bridge, is almost entirely inspired by real aspects of the city, in fact. There really is an early-20th-century bridge which sits partially over a 19th-century graveyard, close to the downtown area. There really is a hospital at one end of the bridge and a luxury hotel at the other. Four thousand graves really were dug up when the nearby motorway went through in the 1960s, and the bodies really were cremated and reburied in a mass grave next to the bridge. And there really is a statue of Zealandia, the personified spirit of New Zealand, a short distance down the road. All of these are key elements of the story in Ghost Bridge; in fact, if you took them away, there wouldn’t be much story left. And I didn’t have to make up a single one of them, only take what was there already and combine them imaginatively.

The other fun thing about Auckland Allies is that I can write in my own dialect. A lot of the time, I’m writing with an eye to the American market, since that’s the largest market for fiction in English, and I have to be aware of phrasing things in a way that will be clear to American readers, not using turns of phrase or slang that come naturally to me but would sound strange to them. In Auckland Allies, I’m writing characters who are explicitly New Zealanders, and they speak accordingly–not only in their dialogue, but in their narration, since I use first person points of view. I’m still aware of the language, and still careful to phrase things so that someone who isn’t familiar with the slang will nevertheless understand it from context–something that, as a science fiction and fantasy author, I have practice at doing–but I enjoy being able to write in a full-on Kiwi voice, rather than in intentionally bland international English.

Hand of the Trickster

Hand of the Trickster is my newest series, so new that I’ve only just published the first book. So far, I have a 34,000-word novella (the one that just went up), and 26,000 words of what looks like being a shortish novel. Accordingly, the setting is less developed so far than in the other two series.

It’s sword-and-sorcery, set in a world of many gods. The High Gods have become distant and uninvolved since the War of Gods, leaving their followers to (mis)manage the Empire, but the Middle Gods are still at large in the world, especially the Trickster.

One thing I enjoy about this setting is that not much is really nailed down yet. I’m making it up as I go along, rather than planning it out in advance (like the Gryphon Clerks) or conforming it to the real world (like Auckland Allies). I haven’t even drawn a map yet. While that results in a setting that isn’t as rich and complex, the focus is more on character and plot; the setting, apart from the situation with the gods, doesn’t drive the story as much as in the other two series.

Having a main character who’s a thief in the service of the Trickster also enables me to let my chaotic side out to play. I’ve met a couple of real-life fraudsters, and they were extremely annoying; but I love fictional heists, capers, and shenanigans, and this is my chance to write some. I identify as neutral good with strong lawful leanings, but writing a chaotic good character like Now You Don’t (the protagonist and narrator of Hand of the Trickster), or like Sparx, the hacker technomage in Auckland Allies, is tremendous fun and gives the mischievous part of me a safe outlet. My father always enjoyed playing villain roles in light opera, for similar reasons.

The Gryphon Clerks

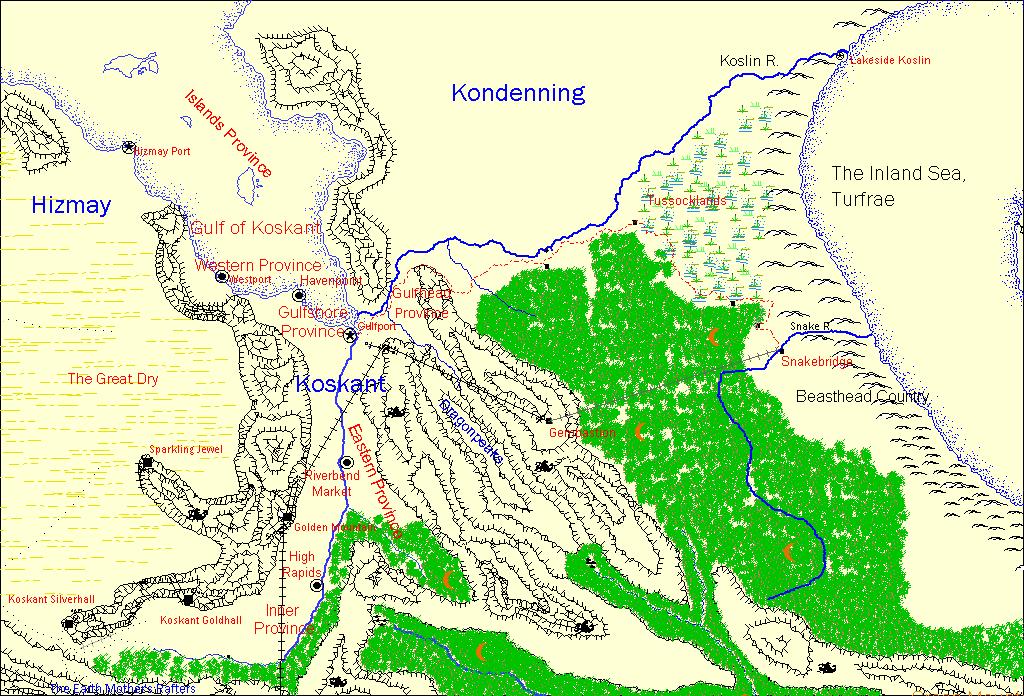

The Gryphon Clerks setting was originally intended as a game setting, but I never finished the game, and the story seeds I kept planting became too tempting. I mapped out a geographically large and culturally detailed and diverse world, with room for a great many stories, and in fact I find that the stories multiply as I write them.

This is partly because lots of minor characters tend to be needed for the kind of large-scale stories I tell there, and they turn up and become unexpectedly interesting, and then I want to write more about them. In the book I’ve just finished drafting, for example (Mister Bucket for Assembly), near the end of the book three young gnomes are running a small newspaper and what amounts to a radio station. They’re secondary to the main action, but now I want to write a novel all about them as they build their media empire, bicker, fall in love, break stories, witness history and struggle against the odds. This is how the world tends to expand, one story at a time, and there’s a whole huge area beyond the mountains that I haven’t even visited yet.

I said above that I worked out the setting in advance. I didn’t work out everything, though. As I write each book, I add to a wiki which holds all of the established facts about the world, so that I don’t end up contradicting myself. Sometimes, this sparks further ideas; occasionally, it means I can’t do something because of something I’ve already said, and I have to rewrite. This generally ends up being a useful creative constraint more than an annoyance, though.

What is a bit of an annoyance, in retrospect, is that I’ve made the setting almost science-fictional, and used some different terms for things that we already have names for, like marriage (which I call oathbinding), in order to underline the differences from our world. I’ve also used an approach to character names that not everybody loves. I’m kind of stuck with those things now, even though they can feel awkward at times. People who love the setting and the characters seem willing to forgive me, though.

Setting and Story

When you’re writing fantasy and science fiction, in particular, setting is very important as a story driver. Not only does it determine what stories are possible, but it suggests what stories might be interesting.

My first published novel, City of Masks, was stalled for about 10 years because, having got the protagonist to the setting, I couldn’t figure out what happened next. My creative block was freed when I made a large diagram of conflicting factions in the city and tied characters to them. Each group, and therefore each character, had its own agenda, and this set the story in motion. I’ve not, so far, thought of another story in that setting, but if I ever do it might well be driven by a similar spring. Certainly, clashing interests in the respective settings drive the plots of Auckland Allies, Hand of the Trickster and the Gryphon Clerks, in different ways that I’ve attempted to explore above.

While immersing deeply into just one world and writing a series, or multiple series, set there has proved a productive and lucrative approach for many writers, I find that variety helps me to stay fresh, and that my different settings have unique elements that make each of them fun in its own way. I hope that my readers find the same.